The growing pains of open scholarship

Published:

As open scholarship becomes more embedded in academic structures, its players are negotiating different challenges that are coming to the fore. Recent discussion in science reform Twitter circles has been about potential conflicts caused by the products of open scholarship (preprints, open data and open code). On the surface, it may appear that open scholarship is causing more issues but here, I’ll suggest that it’s the same old underlying problem, and that the science reform movement should prioritize action on that problem.

The first scenario

Simine Vazire and others in the replies discuss what behaviors should be normed around the use of open data – should the researchers notify the original creators about their reuse of the data, or would a citation without co-authorship be sufficient? Would this vary depending on what the original data is, and how it is being reused? If behavior should be considered situationally, then would it be best for there to be public statements on how the dataset should be used or would that defeat the purpose of open data?

Everyone involved here seems super admirable & non-defensive (see replies). But I worry that pushing this norm, that ppl should notify original authors before reusing publicly available data, will have bad effects for science if/when original authors aren’t as reasonable & noble. https://t.co/PjYssAovQl

— simine vazire (@siminevazire) August 28, 2022

The second scenario

Another incompatibility is the one between open scholarship and double-blind peer review. Since preprints, data and code are usually published without anonymity, the peer review is no longer double-blind if these materials are accessed by the reviewer. Arguably, a reviewer should be accessing the data and code to ensure the computational reproducibility of the results and provide assurance against any errors or fraud. This issue has been known for years seemingly without any progress – see Everything Hertz podcast episode on this very issue in October 2019, and most recently raised by Alon Zivony and I:

Also when reviewers access open data or code usually hosted without anonymity. Don't think it's totally a *problem* though, I think open peer review is underutilized (brings recognition to quality reviewers, allows judgment on the rigor or bias of the review process).

— William Ngiam | 严祥全 (@will_ngiam) August 28, 2022

More open scholarship, more problems?

These two situations appear somewhat disparate – the first is about reuse of open data, the second is about peer review – but they share a complex underlying problem: how do we protect against ‘bad actors’?

- In the first scenario (the analysis of open data by independent scientists), conflict may arise when the original authors are not notified from inadequate recognition of the scientists for collecting the dataset, or may arise when the original authors are notified because the original authors request collaboration, only to stonewall any secondary research project.

- In the second scenario (double-blind peer review at odds with open materials), the scientists may be punished for their open scholarship practices – for example, by a reviewer who chooses to act on some negative bias against the scientists as their identities are revealed, and block the manuscript.

At a fundamental level, the ‘solution’ to these issues for scientists could be fairly straightforward - don’t be assholes to each other. Perhaps naïvely, I’d be surprised to find a scientist who isn’t excited to share their research with others and collaborate when there’s a good reason to do so, or be honored to hear about someone using their collected data to further scientific understanding. A reviewer could adhere to double-blind peer review by simply not seeking the open materials of the associated manuscript, or acknowledging their potential bias and rigorously ensuring the quality of their review. The assholes are secretive or entitled scientists gaming the system for personal gain.

It’s not us, it’s the…1

Save for changing and aligning the values and goals that all of academia’s players hold, this helpful article by the Donella Meadows Project2 suggests that the next effective place to intervene is to change “the rules of the systems (such as incentives, punishments, constraints)”. There are many incentives in science – some nebulous motivations like prestige, recognition and prosocial hope, and some concrete values like citations, salary, promotion and tenure. These are all most infamously captured by the ‘publish or perish’ aphorism – the increasing pressures on scholars to pad their CVs with first-author papers or otherwise be denied an academic career. I don’t think I need to convince you that authorship can no longer be the metric by which scientists are evaluated; it’s arguably one of the main precursors for science’s reproducibility crisis and needs to be changed (but if you do need convincing).

So, how do we change the rules? I think it is fairly straightforward: all research contributions need to be transparently documented and meaningfully recognized. We simply need to know what is done, and reward what is done accordingly. And there’s already a step we can take towards that: norming a contributorship model in science, and rebuilding our incentives around it (Contributorship, not authorship.)

CRediT where credit is due

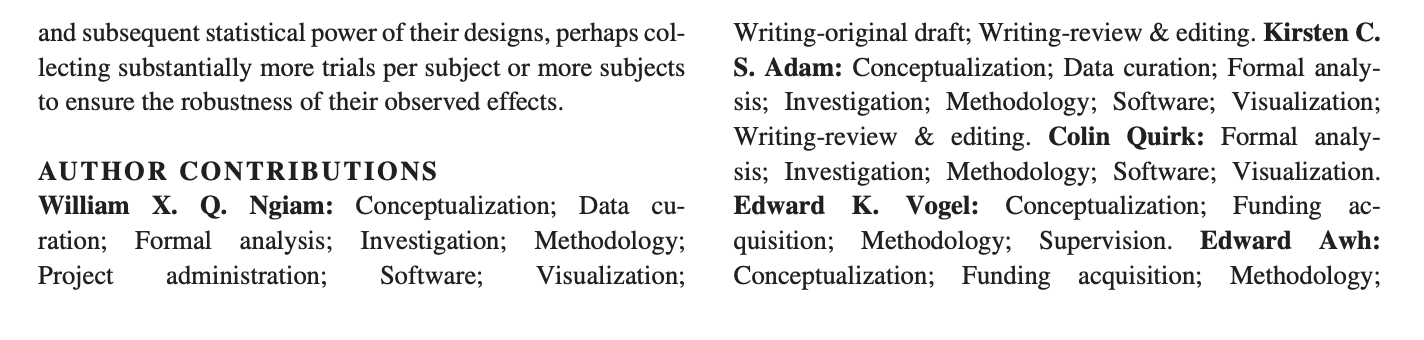

CRediT stands for the Contributor Roles Taxonomy, a proposed set of 14 roles that span the possible contributions to scientific research. These roles are conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, software, supervision, validation, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing. It goes beyond authorship by listing each research contribution, as defined by the CRediT roles, alongside the author names.

An example of how author contributions are listed on a scientific journal article - taken from https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.13791.

An example of how author contributions are listed on a scientific journal article - taken from https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.13791.

Let’s return to our two scenarios and apply CRediT:

- In the first scenario, conflict could be avoided by setting a standard that adequately recognizes the contribution of open data to science. I believe that this means awarding authorship under the CRediT model – specifically in the Investigation role. This may run adverse to many readers’ opinions because it’s quite a radical shift from our current model; to award authorship to other people that collected the data. There’s an unease that someone could get a lot of ‘papers’ from having their open data used…but that unease is what we want because it may push scientists to create and value open datasets! Imagine the improved resourcefulness in science from double-dipping into existing datasets, and how that may better redistribute our limited resources! It might better incentivize scientists to collect rigorously controlled, high quality, registered datasets if they know their hard work will be rewarded!

- In the second scenario, I think science’s main self-correcting mechanism can be totally transformed. I think we should have open peer review because that allows scientists to evaluate the quality of the review, but also we can recognize the reviewers for the contents of their review as a contribution. Consider a Registered Report where a reviewer improves the rigor of the data collection process – I think they can be listed under the Methodology role of CRediT. If a reviewer ensures the reproducibility of the analysis code, I think they should be credited under the Software role. If this is too messy, I think expanding CRediT to include a role like quality assurance is a good idea! I think science could even perhaps consider action editors being allowed to assign the contributions. This all means that the very important work of ensuring science’s rigor and self-correction becomes transparent and incentivized, when it very much is not currently.

I think this presents a hopeful vision – a structure of science that would reward the collection of well-used reproducible datasets and code, that would incentivize the currently invisible and undervalued work of peer review, that would promote the values of open science like rigor, collaboration and transparency.

So, what are we waiting for?

Many scientists think it’s a great idea (check out the replies to the idea on Twitter), and CRediT is already adopted by many publishers such as the Public Library of Science (PLOS), eLife and Cell Press (see list here: https://credit.niso.org/adopters/). It’s a matter of getting everyone in the know and establishing CRediT as standard across science – norming its use across all levels and contexts. Here are my ideas on ways this can be achieved:

For individual researchers:

- Discuss with your research collaborators about their contributions within the CRediT framework, ideally at the begining of your next project. The tenzing app is a useful online tool for organizing contributions and automating the output.

- Promote CRediT within your lab, including having open discussions with the head of the lab as to what should be credited as a contribution.

- Conducting metascience research with the CRediT metadata.

- Add CRediT to your academic CV to denote the contribution you made in each publication.

An example of how CRediT contributions could be listed on an academic CV.

For institutions:

- Mandate the use of CRediT for all research outputs, ensuring all contributors are fairly and equitably recognized.

- Make assessments on contributions to research rather than publications. This could be when awarding graduate students with their degrees, tenure and promotion criteria, or perhaps most importantly, employing based on needed and potential contributions to research outputs rather than arbitrary standards and ‘fit’.

For societies/publishers:

- Standardizing and highlighting the research contributions with any submission. At conferences, this could be publishing abstracts with research contributions rather than authors, and encouraging presenters to display the CRediT roles on their talk slides or posters.

For funding agencies:

- Creating an option on grant applications to list and employ research specialists to fulfil the CRediT contributions, say programming or statistical analysis.

Final credits…

I truly believe that by standardizing CRediT, we will be taking the first step towards fixing the broken incentives in academia. And with that, by recognizing all research contributions and having them open to see, we can hope to rebuild our science ecosystem to one that promotes more rigorous and impactful science, and equitably values all its contributors.

References and Further Resources

Holcombe, A. O. (2019). Contributorship, not authorship: Use CRediT to indicate who did what. Publications, 7(3), 48. https://www.mdpi.com/2304-6775/7/3/48.

The tenzing tool automates the author contribution text output to add into your next research manuscript. Link to tenzing ShinyApp See: Holcombe, A. O., Kovacs, M., Aust, F., & Aczel, B. (2020). Documenting contributions to scholarly articles using CRediT and tenzing. PLoS One, 15(12), e0244611. - https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0244611

I wrote an article on how contributorship may address marginialization of early-career researchers in scientific publications, “Fully Credited: Making Publishing More Equitable”.

If you’d like to hear early-career researchers perspectives about CRediT, Sarah Sauvé and I chat about it on the ReproducibiliTea Podcast:

Some further information on implementing CRediT, hoested by the National Information Standards Organization (NISO): (https://credit.niso.org/implementing-credit/).

1 incentives. A reference to Tal Yarkoni’s famed blogpost – “It’s not The Incentives, it’s you”.

2 Thank you to Gavin Taylor and the Nowhere Lab for sending me this useful article on how to change systems. Further thanks to them for allowing me to lead a meeting and discuss this blogpost!